In 1858, a groundbreaking discovery was made by British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace near Bali. Little did he know that his findings would change the course of science forever.

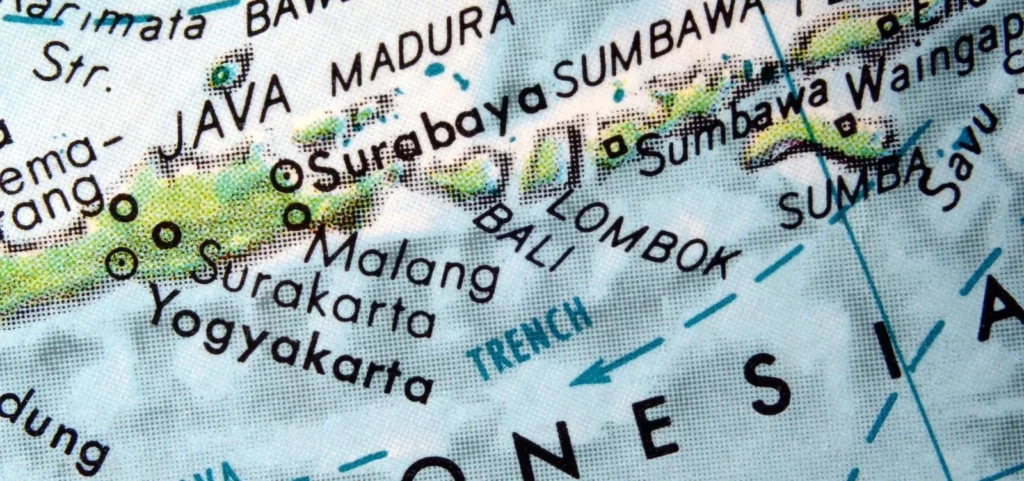

As Wallace navigated the Malay Archipelago, he noticed something astonishing – an invisible barrier separating species on either side of the Lombok Strait. This phenomenon would later be known as Wallace’s Line. The significance of this discovery cannot be overstated; it fundamentally altered our understanding of evolution and the natural world.

Wallace’s observation was simple yet profound: despite their proximity, Bali and Lombok are home to distinctly different fauna. What might have driven this drastic separation? A closer examination of geological history provided the answer. Prior to the last Ice Age, sea levels fell dramatically due to the cold climate, connecting Southeast Asian islands to the mainland. This allowed species to migrate freely.

However, a crucial detail emerged – the deep waters of the Lombok Strait never dried up, serving as an impassable barrier that prevented species from crossing. Fast forward to the present day, and we can see the consequences of this historical event in stark contrast between animal populations on either side of Wallace’s Line.

The implications are nothing short of extraordinary. The discovery of Wallace’s Line not only reshaped our understanding of evolution but also expedited the publication of Charles Darwin’s groundbreaking work, On the Origin of Species. In essence, Wallace inadvertently hastened the revolution that would come to define our understanding of the natural world.

As we delve deeper into the significance of this phenomenon, it becomes clear that species on either side of the boundary have evolved in isolation for millions of years. This is exemplified by the stark differences between the crab-eating macaque and the booted macaque. The former, found west of Wallace’s Line, boasts a long tail adapted to its arboreal lifestyle, whereas the latter has developed a more robust body and shorter tail suited to the dense forests of Sulawesi.

The effects of this separation extend beyond physical adaptations; behavioral differences have also emerged. While crab-eating macaques are opportunistic and willing to raid human settlements, their eastern counterparts remain reclusive, relying on the resources of Sulawesi’s forests.

Moreover, fossil records reveal an ancient lineage confined to the Sunda region, with some species dating back 30-40 million years ago. This long-standing separation suggests that island arcs and shifting landmasses may have once provided a pathway for dispersal, only to become isolated through geological changes.

It is crucial to note that not all species are bound by this invisible boundary. Certain bat species, capable of traversing water barriers through flight, have successfully crossed Wallace’s Line, adapting to new environments in the process.

Wallace’s discovery highlights the awe-inspiring diversity within our planet’s natural world. As we continue to learn more about the intricacies of life on Earth, it is essential that we appreciate and respect this incredible tapestry of life.